there's something about Mali

This post was written as part one of a series on African music for the ace development blog Hii Dunia (click here for details).

When talking about music in Africa, it is inevitably Mali that first comes to mind. The landlocked, flat country in the heart of West Africa has become synonymous with expressive, beautiful music with a capacity to cross over and win the hearts of Western enthusiasts. In the last seven years Malian music has swept all before it and threatened, for the first time since the early 1980s, to push African music back into popular culture in the UK and Europe. So why is the music of a land so arid so musically fertile? And where should the novice start? When Ali Farka Touré died in March 2006, it was predictable that the world music community would greatly mourn the loss of perhaps Africa's greatest and most recognisable guitarist. What was slightly more surprising was that coverage of his passing extended far beyond specialist music magazines and into the main pages of the international press. Farka Touré's legacy, besides a run of stunning records, is that he carried the torch for Malian music. Yet he is not alone. Amadou et Mariam, Toumani Diabaté and Salif Keita all mine the rich vein of musical history in one of the world's poorest nations, combining artistic endeavour with critical and commercial acclaim.

When Ali Farka Touré died in March 2006, it was predictable that the world music community would greatly mourn the loss of perhaps Africa's greatest and most recognisable guitarist. What was slightly more surprising was that coverage of his passing extended far beyond specialist music magazines and into the main pages of the international press. Farka Touré's legacy, besides a run of stunning records, is that he carried the torch for Malian music. Yet he is not alone. Amadou et Mariam, Toumani Diabaté and Salif Keita all mine the rich vein of musical history in one of the world's poorest nations, combining artistic endeavour with critical and commercial acclaim.

Why so many wondrous artists? This is not an easy question to answer. A former French colony which is now one of the most politically and socially stable in Africa, Mali saw many of its finest musicians, like The Rail Band and Les Ambassadeurs decamp for the Ivory Coast in the late 1970s, driven away by the poor economic climate. Yet others, such as the extraordinary Albino folk singer Salif Keita, headed for Paris - and helped give root to a climate of cross-cultural exchange between states previously master and servant. They were joined in Paris by the likes of Nigerian drummer Tony Allen, whose own contribution to the development of international music - and hip hop - cannot be understated. In Paris Keita developed and updated the Mande sound, expunging the Cuban influence which had been dominant since the 1960s, and introducing - much to Charlie Gillet's distress - the sound of synthesisers. Inspired by the mande sound, Parisian record labels - and London's World Circuit - rushed to document these new sounds. Back in Mali, and shortly to benefit from the rapidly rising profile of Keita and emerging stars such as the splendid duo Amadou et Mariam, who also served their musical apprenticeship with Les Ambassadeurs, the jeliya, or Griot, caste of Malian singers and storytellers (of which the wealthy Keita is not a member) built on the extraordinary legacy of their unique role in Malian culture. Most closely resembling bards, the Griots are wandering musicians and poets, who pass down their skills from generation to generation. They are endogamous, meaning that they do not marry outside their tribes, and as a consequence names recur as if they were enthusiastic recommendations - common and familiar surnames include Kouyaté, Kamissoko, Cissokho, Dambele, Soumano, Kanté, Diabaté and Koné.

Back in Mali, and shortly to benefit from the rapidly rising profile of Keita and emerging stars such as the splendid duo Amadou et Mariam, who also served their musical apprenticeship with Les Ambassadeurs, the jeliya, or Griot, caste of Malian singers and storytellers (of which the wealthy Keita is not a member) built on the extraordinary legacy of their unique role in Malian culture. Most closely resembling bards, the Griots are wandering musicians and poets, who pass down their skills from generation to generation. They are endogamous, meaning that they do not marry outside their tribes, and as a consequence names recur as if they were enthusiastic recommendations - common and familiar surnames include Kouyaté, Kamissoko, Cissokho, Dambele, Soumano, Kanté, Diabaté and Koné.

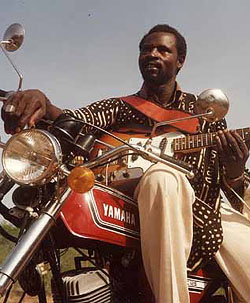

By this time Farka Touré, still unknown outside Mali, got a job as a sound engineer at Radio Mali. Taking advantage of the opportunity to record his songs, he began sending out cassettes and Sono Discs were quick to release them. By 1994 he had been championed by Gillett, Andy Kershaw and - crucially - Ry Cooder, who recorded the groundbreaking 'Talking Timbuktu' with him. It was a revelation, although one which the level-headed Touré did not allow to obstruct his life. He returned to his home town of Niafunke, becoming mayor and concentrating on farming, allowing music to retreat into the background.

Yet the genie was out of the bottle. Touré was not the only musician with devastating talent in Mali. Record labels swiftly picked up on stunning albums by the likes of Toumani Diabaté, a master on the Kora (a 21 stringed harp-lute), Boubacar Traoré, another rootsy, blues-flecked exponent of the desert blues, and Touré's protegy, Afel Bocoum (who later collaborated with Blur's Damon Albarn on his well received 'Mali Music' LP). Despite the success enjoyed by these artists, in his later years Touré remained unconvinced that the youth of Mali (who in fact were more often engaged with the sound of wassoulou artists such as Oumou Sangaré) appreciated the Griot tradition sufficiently. Keen to put things right, he launched into a prolific late surge of recording activity which yielded perhaps his greatest material yet, notably his delicious collaboration with Diabaté, 'In The Heart of The Moon', and last year's final, peerless, 'Savane'. Despite his death, 2007 is as good as time to listen to Malian music as ever. Amadou et Mariam, given a sprightly, pop polish by Spanish producer Manu Chao, are writing and recording the most heartfelt and gorgeous songs of a long career, and recent releases by Bassekou Kouyate and Ngoni ba, along with a sparkling debut by Vieux Farka Touré, the son of the great man himself, promise great things. Best of all, it seems that Tinariwen, the strangest and most original of Mali's new bands, are on their way to bona fide international rock stardom. If things did go that way, it would be no surprise. Writing from the desert Tourag tradition, Tinariwen - who formed in the rebel camps of Libyan leader Col. Gaddafi - are the first band of their ilk to play the desert blues with electric guitars. Their astonishing sound, which combines hypnotic rhythms, call and response vocals and uncompromising guitar, sounds truly unique - primal and rebellious, leading to (fatuous) comparisons to the White Stripes and (perhaps legitimately) The Clash.

Despite his death, 2007 is as good as time to listen to Malian music as ever. Amadou et Mariam, given a sprightly, pop polish by Spanish producer Manu Chao, are writing and recording the most heartfelt and gorgeous songs of a long career, and recent releases by Bassekou Kouyate and Ngoni ba, along with a sparkling debut by Vieux Farka Touré, the son of the great man himself, promise great things. Best of all, it seems that Tinariwen, the strangest and most original of Mali's new bands, are on their way to bona fide international rock stardom. If things did go that way, it would be no surprise. Writing from the desert Tourag tradition, Tinariwen - who formed in the rebel camps of Libyan leader Col. Gaddafi - are the first band of their ilk to play the desert blues with electric guitars. Their astonishing sound, which combines hypnotic rhythms, call and response vocals and uncompromising guitar, sounds truly unique - primal and rebellious, leading to (fatuous) comparisons to the White Stripes and (perhaps legitimately) The Clash.

Touré is gone, but there is no need for despair - whichever twists, trials and challenges face this remarkable country, the music always survives. There's just something, it seems, about Mali.

original post accessible here.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

1 comment:

MALI LATEST NEWS ON

http://www.niger1.com/mali2.html

moub21@gmail.com

Post a Comment